Ward: Fantasies & Verse Anthems

Phantasm

Recording Date: 6-9 May 2013

Recording Location: Chapel of Magdalen College, Oxford, UK

Producer: Philip Hobbs (fantasies) and Adrian Peacock (anthems)

Engineer: Philip Hobbs

Post-Production: Julia Thomas

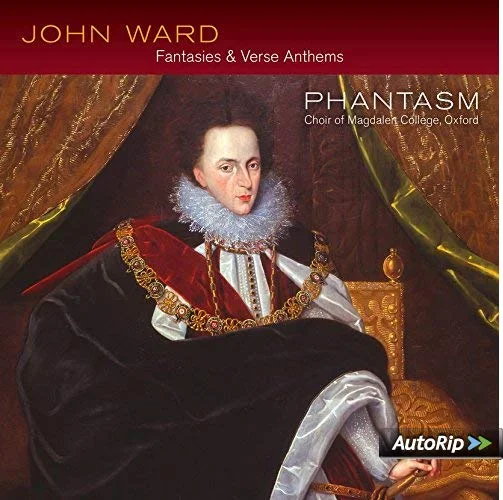

Cover image: 'Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales' with permission from the President and Fellows of Magdalen College, Oxford

Design: gmtoucari.com

The four-part viol fantasies complement Phantasm's previous recording of Ward's five- and six-part works and show an equally fluent and skilful style exemplifying Jacobean consort fantasy at its best. The Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford directed by Daniel Hyde, join Phantasm to perform Ward's verse anthems which contain an ever-shifting kaleidoscope of textures and generous word painting amidst a polyphonic swirl of viols. Phantasm are also joined by Emily Ashton and Christopher Terepin for this performance.

This recording is a fitting tribute to John Ward, whose efforts have been rediscovered in our own time and whose mellifluous music deserves a closer look. Phantasm's illustrious recording career has resulted in the viol consort being repeatedly recognised at the Gramophone Awards with two Awards and several ‘Finalist' nods to its name.

Phantasm's debut on Linn, Ward: Consort music for five and six viols was named a ‘Choice' recording by BBC Music Magazine whilst also receiving many five and four star reviews.

Fantasies a4 & Verse Anthems

In his ambitious and accomplished music for voices and viols, John Ward (c.1589-1638) offers a privileged glimpse of a special moment in English music history. Composed perhaps during the years 1609-16, these verse anthems and viol fantasies were penned by a young ‘gentleman' composer attached to the household of a highly cultivated Italianophile, Sir Henry Fanshawe of Warwick Lane, London and Ware Hall, Hertfordshire. Fanshawe was an avid collector of musical instruments and works of art, an aristocrat linked (through his position as Remembrancer of the Exchequer) to the most aspirational and culturally alert member of the British royal family, the young Henry Frederick Stuart (1593-1612), Prince of Wales. Ward came to the Fanshawe family in 1607 after serving as a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral before being admitted to its grammar school. Not only were consorts of viols cultivated in the prince's entourage, but verse anthems - an inspired fusion of the polyphonic liturgical anthem, the anglicized Italian madrigal style and the native viol fantasy - were especially connected to the prince's musical establishment.

Had Prince Henry not died suddenly at the age of 18 in 1612, Fanshawe (it was later reported) would have succeeded to high office in the royal court, perhaps with John Ward in tow. Rejecting the fastidious and ever-changing vagaries of French fashion, he led his own lustrous court, complete with a separate musical entourage of leading composers, including Thomas Ford, John Bull, Robert Johnson and Thomas Lupo; the prince was even reputed to have been taught the viol by Alfonso Ferrabosco II. According to a posthumous memoir from 1634 by William Haydon, a former Groom of the Bedchamber, Henry especially ‘loved Musicke, and namely good consorts of Instruments and voices joined together'.

How striking, then, that this fondness is recorded in Ward's anthem This is a joyful, happy holy day, composed most likely for the lavish Whitehall entertainments celebrating Henry's investiture in 1610 as Prince of Wales*. On this festive day, all are invited ‘to sing in consort with sweet harmony of instruments and voices' melody'. In its mention of a ‘consort' and the combination of ‘instruments and voices' the text alludes to its own setting. Listening to the ever-shifting kaleidoscope of textures in these anthems, one hears in each section how the viols foreshadow the sung melodies that introduce highlighted vocal solos in a serious and Italianesque madrigal style, full of generous word-painting. Finally the chorus enters, doubled by the consorts of viols, the assembled unity confirming and elaborating both text and melody.

The mention of musical harmony in the context of Henry's investiture as Prince of Wales might seem just a banal metaphor, but the documentary evidence suggests a tremendous expectation attached to Henry's future: that view is retrospectively confirmed by the extraordinary outpourings of poetic and musical laments following his untimely death. William Byrd's consort song on Henry's death, Fair Britain Isle, for example, asserts that with the prince's death there ‘died the hope of age of gold'. Moving backwards in time to 1610, one can reasonably guess that polyphonic music offered an idealized reflection of the wildly optimistic prediction that Henry's future reign as king would usher in a golden age of contentment and prosperity. Indeed, in a 1605 song by Thomas Ford dedicated to the 12-year-old Prince Henry, for example, the text defines a ‘commonwealth' as ‘a well-tuned song where all parties do agree'.

Coincidentally, 1605 was the same year in which Henry's educational aspirations - not, apparently, supported by his hunt-loving father - brought the prince to Oxford, where he matriculated at Magdalen College and was assigned the tutor in Hebrew to look after him. (Henry went up to Magdalen rather than to Christ Church because his influential tutor, Sir Thomas Chaloner, who had set up an academy of aristocratic youths around Henry in 1603-4, was a Magdalen man.) He does not seem, however, to have stayed very long at Magdalen, though the college's choir director (then as now the ‘Informator Choristarum'), Richard Nicolson, like Ward composed verse anthems with viols, some of which seemed to have been performed in chapel. It would be unthinkable that an Oxford college with a connection to a member of the royal family would not have performed music connected to its illustrious junior member. What is more, the considerable number of manuscripts of viol fantasies and verse anthems copied in Oxford attests to a lively interest in these genres during the years leading to 1627, when Nicolson was appointed the first Music Master in the university by the endowment of William Heyther (or Heather), with a collection of 40 music books and a chest of viols to be played at least once weekly in the university's Music School.

These considerations only bear on the final piece on this recording. But in addition to the celebratory work for the princely investiture, Ward's verse anthems for voices and viols embrace psalm settings and devotional pieces with a decidedly Protestant bent, and in doing so reflect Prince Henry's special interests. Ward's verse anthems are remarkable for the clarity of their text-setting: these works - more than, say, those by Orlando Gibbons - show a love of roving solos and duets which keep up the interest as ever new voices enunciate the words amidst the polyphonic swirl of the viols before choral repetitions hammer home highlighted lines of verse. The tone is decidedly serious, and what is astonishing is that the madrigalisms - or musical word-painting - create an effortless poetic effect and never raise ironic eyebrows in the way that secular English madrigals prompt a twinkling of the eye through their love of frivolity. Like Ward's own serious collection of published madrigals (1613), which is dedicated to Fanshawe and notes its composer's disdain for ‘Time-sicke humourists', the anthems strike a sombre tone of piety; but it is one that revels in warmly lyrical outbursts, and never succumbs to puritanical restraint or censorious anxiety about music's expressive gifts.

The six-part Praise the Lord, O my soul (here reconstructed by Ian Payne) sets Psalm 104 (less its final verse) and is a song reimagining the story of Creation in Genesis. Ward's madrigalian instincts seem to await such obvious musical tone-painting as ‘They go up, as high as the hills, and down to the valleys beneath', with musical contours that aptly ascend and descend. But even here the composer does far more than just craft melodic shapes. The miraculous act of God that commands the inchoate waters of the earth to rise does so in image-laden stages in the music: first the waters ‘go up' on their own, as if it is enough to admire that marvel; only thereafter do the musical waters climb ‘as high as the hills', and then, as in a choreographed bodily gesture, move ‘down to the valleys beneath'. The imitative reiterations of clearly stated snippets of text act therefore almost as gestured incantations, which illustrate by constant rehearing the most salient poetic images. The literary voice is not merely that of the singular psalmist but of an angelic consort of musical praise. In fact, Ward's frequent repetition of musical ‘points' or motives with their accompanying snippets of text has a way of inducing (mantra-like?) a mildly hypnotic state that both extends and enriches the listener's experience.

Ward also underscores passages of text by memorable instances of rhythmic declamation; that is, by forging melodic and rhythmic identities for the given words. So, for example, the opening lines of Psalm 104 are clearly anticipated by the wordless viols, who have already accented ‘Praise', ‘Lord' and ‘soul' in naturalistic English without the words' having yet been heard. When the duo of treble voices enters, the ear accepts - and the mind trusts - the word setting because the anticipatory imitation in the instruments has already seeped into semi-consciousness. Yet not every line is set naturalistically: note the exciting octave leap upwards on the words ‘thou art': here the artifice of an ‘incorrect' declamatory leap effects a musical experience of surprise and awe that projects attention on to the words that follow - ‘exceeding glorious' - since it is semantically incongruous to accent the verb here: ‘thou art become exceeding glorious'.

The grand poetic journey of creation that begins in high heaven and ends on the earth below is also mirrored by the fall in the vocal range of the paired duets: first trebles, then tenors, then basses, the last best suited to frighten us with their deep ‘rebuke' and subterranean vision of dark ‘thunder'. Ward even has the singers exhibit the fear of the anthropomorphized waters, who are ‘afraid' of the Lord in the midst of his magisterial acts of creation. In a similar fashion, the composer affirms the affective safety of the earth's immutable ‘foundation' by his agogic emphasis on the first syllable of ‘never [should move at any time]': no doubt, here, that both psalmist and listening believer stand on the most secure ground of terra firma!

Verses with solo voices invariably give way to a ‘chorus', labelled as such in the surviving sources. Here the frequent use of homorhythmic declamation advances a different musical argument, that of iterative unanimity: were there some difficulty in deciphering words in the verses - though which good Anglican would not know the psalms by heart? - then the opening of these choral entries reveals a host of angels who speak with one synchronized voice.

The viols not only adumbrate the text but also give space and time for the establishment of what Jacobeans referred to as the ‘air': the setting of a mood as well as a meditation on the words just sung. In the paired anthems that begin with the very Italianate descending utterance Down, caitiff wretch, the viols begin as if playing an independent viol fantasy, thereby occluding the point of melodic imitation which follows. Their presence also encourages some serious word-play: in the line ‘whilst heav'nly thoughts do Discant on the ground', Ward alludes to the improvisatory genre of instrumental music - treble variations or ‘divisions' on a bass theme or ‘ground' - by having the bass hold a long one-note ‘ground' while two trebles sing lithe ‘descants' in close canon above. He also alternates madrigalisms with musical illuminations or heightenings of individual words. Ward the madrigal composer sets three voices for the ‘blessed Trinity', low notes for ‘lowly creep', fluttering quavers on ‘winged faith' and a unison accent on ‘one accord'; Ward the rhetorical musician-interpreter also accents the setting of ‘angels', which rips the word from its context so as to celebrate an awestruck and sudden intrusion of a seraphic choir who offer praise in song, vision and gesture. The four-part viol fantasies complement Phantasm's recording of the five- and six-part works (Linn CKD 339) and show Ward composing in an equally fluent and skilful vein. Composed for one treble, two tenors and one bass viol, these six pieces exemplify the Jacobean consort fantasy at its best: experimental in its love of angular, even unsingable themes stated in double counterpoint; of demarcated sections set off by full cadences and rests; of forays into neighbouring keys; and of moments of madrigalian harmony to which conventionally melancholic, even Italian, words might be supplied by the literary imagination. As a group, the works seem to become ever more complex from Fantasy 1 to Fantasy 6.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that for the final work, Fantasy 6, we possess the only seventeenth-century description of a piece of English consort music. In a letter from 1658, Dudley, Baron North of Kirtling, writes to one of his employees about Ward, and refers to the C major Fantasy's ‘brisk, lusty, yet mellifluent vein...that stirs our bloud, and raises our spirits, with liveliness and activity, to satisfie both quickness of heart and hand'. The work stands out (even for Ward) in its extended range - it makes use of a top C (c ) in the treble and a bottom C in the bass - as well as for a brief passage in triple time, which perhaps borrows an idea from Gibbons's most modish four-part works. But what is fascinating in Dudley North's characterization is that the quick tempo of the piece - nowhere marked as such but implicit in the note values - was heard as full-blooded and lusty yet at the same time flowing smoothly like honey (‘mellifluent').

Whereas so many of Ward's works are sombre and in the minor mode, Fantasy 6, in the sunniest key of C, not only stimulates players - the composer focuses on executants rather than listeners in mentioning their ‘hand' - but dispels melancholy. By way of its sanguine temperament, the ‘liveliness and activity' of the fantasy ‘raise spirits' and provide ludic satisfaction. It is as if the viol fantasy, which of its nature requires multiple participants, supplies a miraculous tonic that rejuvenates the spirit by embodying a hopeful ‘activity' emblematic of the ideal human condition. In mastering the environment by the skilful use of one's hands and engaging one's heart as well, the consort exudes an equable temperament and a sympathy for humankind. Having played this piece himself, North experienced his world as ‘well-tuned': quite a compliment to pay a remnant of a composer's imagination lasting less than three minutes. This lovely encomium for a mostly forgotten piece of music from the second decade of the seventeenth century is brief, but a fitting tribute to John Ward, whose efforts have been rediscovered in our own time and whose mellifluous music deserves a closer look. © Laurence Dreyfus, 2014

*Though scholars seem unsure whether the piece was written for Henry in 1610 or his younger brother Charles in 1616, Fanshawe forged connections with Prince Henry's entourage, and in fact died in 1616 several months before Charles's investiture. Fanshawe's son Thomas was apparently little interested in music, so it would seem odd that a piece by the gentleman John Ward, not otherwise attached to a royal household, would make its way to a court entertainment after Henry Fanshawe's death.

Editions:

The Complete Works for Voices and Viols in Five Parts ed. Ian Payne (Corda Music Publications 429, n.d.)

The Complete Works for Voices and Viols in Six Parts ed. Ian Payne (Corda Music Publications 458, n.d.)

Consort Music of Four Parts ed. Ian Payne (Musica Britannica 83: Stainer & Bell, 2005)*

*The tracklisting gives numberings from the Viola da Gamba Society's thematic index for ease of reference.

Interview with Laurence Dreyfus on Ward: Fantasies & Verse Anthems by Toccata (In German)

Herr Dreyfus, Sie haben mit Ihrem Gamben-Consort Phantasm und dem Magdalen College Choir Oxford unter Leitung von Daniel Hyde eine neue CD mit Verse Anthems und Fantazias von John Ward eingespielt. Was kann man sich unter der Musik auf dieser CD vorstellen, in welches historische und musikalische Ambiente wird man da versetzt?

Wir sprechen über Musik aus dem frühen 17. Jahrhundert in England, einer Zeit, in der die Mode aufgekommen war, Stimmen und Gamben zusammen zu bringen. Und gleichzeitig wurde auch auch das Gamben-Consort immer beliebter und breitete sich immer weiter aus: Hatte man diese Tradition vorher nur an den Königshöfen und den Universitäten gepflogen, so spielten nun auch immer mehr reiche Leute auf dem Lande diese Consortmusik - das wurde zu so einer Art Home-Entertainment-Center... Dass man zu diesem Consort nun auch sang, war ein Aspekt, der es erlaubte, sowohl säkulare Musik - wie Madrigale - einzubeziehen, aber auch ernstere Musik, wie die Verse Anthems, die wir auf dieser CD eingespielt haben. Das sind Stücke mit nicht-liturgische Texten, Psalmen und Andachtslieder.

Die waren aber nicht für den Gottesdienst bestimmt?

Nein, nicht für den Gottesdienst - aber ebenso wenig waren diese Stück ausschließlich für die Verwendung bei Hofe bestimmt. Es ist also eine Art Musik für Kenner, zum Beispiel für reiche Familien, die auf in ihren Anwesen in London oder ihren Landhäusern einen Komponisten oder Musikmeister angestellt hatten, oder die einfach einen Satz Gamben hatten, um mit der Familie zu musizieren. Die dürften sich dann also mit ihren Instrumenten versammelt haben und alle spielten oder sangen aus Stimmbüchern. In größeren Institutionen, oder an den beiden Universitäten in Oxford und Cambridge hatte man dann Chöre, die diese Musik aufführten - oft begleitet von Gambe-spielenden Fellows dieser Colleges. Damit haben wir ein sehr klar abgegrenztes gesellschaftliches Milieu, in dem diese Musik verortet war - die also sowohl in kammermusikalischem, als auch in größerem gesellschaftlichen Rahmen erklang.

Was erwartet die Hörer da hinsichtlich Strukturen und Formen: Ist die Musik beispielsweise homophon oder polyphon?

Das ist samt und sonders absolut reinste Polyphonie. Interessant ist aber, dass es sich um Polyphonie handelt, die beginnt, sich für Durchhörbarkeit [audiability] zu interessieren. Wir haben also das Gamben-Consort, das den Chor begleitet, aber auch einleitet - als würden sie selbst ohne Worte bestimmte Arten von Melodien mit imitativen Themen singen. Dann gibt es Solisten im Chor, die den Text in geradezu barocker Manier einführen, bevor der Chor einsetzt und dann im Wechsel mit den Solisten singt. Das ist eine extrem kunstvoll ausgefeilte Klangwelt, in der die Strukturen sich ständig verschieben: Als würde man die Stimmen in diesem polyphonen Satz orchestrieren. So folgt diese Musik also nicht getreulich dem Ideal reinster Renaissancepolyphonie, in der die Stimmen, die Linien alle durchgängig gleichberechtigt sind, sondern sie spielt eben auch mit diesem Sinn für im Dienste der Musik ständig changierende Klangfarben und Nuancen. Das ist absolut faszinierend zu hören, denn es ist so kurzweilig, diese Wechsel zu hören: Zwei Soprane, zwei Tenöre, dann zwei Bässe, dann wieder der Chor oder die Gamben, alle in ständig wechselnden Kombinationen.

Ist das denn nun Musik, die für Chor geschrieben ist, oder für Solisten - vielleicht sogar für Frauenstimmen?

Das ist durchaus möglich, dass gerade in den Landhäusern auch Frauen diese Musik gesungen haben - aber selbst dann wissen wir von Morley und aus anderen Quellen, dass vor allem die Knaben in den Familien sehr früh im Singen und Notenlesen ausgebildet wurden, und außerdem sangen die Männer häufig im Falsett, also als Countertenöre. Im familiären Umfeld, auch in Andacheten, könnten aber durchaus Frauen beteiligt gewesen sein - während das bei Hofe oder auch an den Universitäten sicher nicht der Fall war. Ich kann mir auch überhaupt nicht vorstellen, warum ein Komponist seine Musik ausdrücklich nicht solistisch aufgeführt hätte haben wollen. Auf der anderen Seite wissen wir, dass zum Beispiel Richard Nicholson, der exakt in dieser Zeit Chorleiter am Magdalen College Oxford war und selbst diese Art von Musik für Stimmen und Gamben schrieb und natürlich aufführte, das selbstverständlich mit dem Chor tat. Wir wissen, wieviele Knaben und wie viele Männerstimmen damals da gesungen haben, und das waren mehrere pro Stimme. Auch sind in den Noten die Soli klar bezeichnet, und man findet in den Quellen auch das Wort Chorus. Natürlich könnte man nun darüber diskutieren, was mit Chorus gemeint ist, aber ich kann mir keine Szenerie vorstellen, in der Ward die Interpreten angefleht hätte, seine Musik doch bitte nicht mit mehr als einem Sänger pro Stimme aufzuführen... Nein, ob solistisch, oder chorisch: Das war beides möglich und üblich; das ist keine Frage in diesem Genre, und war auch nie ein Streitpunkt, bis ein paar Musikwissenschaftler im 20. Jahrhundert anfingen, sich darüber Gedanken zu machen.

Was wir ganz sicher wissen, ist aber, dass es bei den Gamben immer nur eine pro Stimme war - es gab keine Gamben-Orchester!

Nun erlebt die englische Musik der Renaissance ja in den letzten Jahren ihrerseits eine Renaissance bei deutschen Kirchenchören - also Amateurchören: Immer mehr Gemeinden veranstalten Evensongs, und auch englischsprachige Psalmen erfreuen sich größter Beliebtheit. Ist diese Musik von Ward denn nun auch ein Repertoire, das für einen solchen Rahmen interessant sein könnte, eventuell sogar begleitet von Amateurgambisten, oder ist sie dafür zu schwer?

Nein, gar nicht, das ginge sehr gut. Interessanterweise sind allerdings einige der Fantazias für Gamben-Consort auf unserer Aufnahme ziemlich anspruchsvoll: Da bin ich mir sicher, dass sie für ausgebildete Musiker gedacht waren. Aber die Stimmen in den Verse-Anthems sind fast alle sehr leicht, sehr lyrisch, und lassen sich wunderbar auch von Amateuren spielen. Das muss auch Teil dieser Tradition gewesen sein, dass die Gambenstimmen auch von nicht-professionellen Musikern gespielt werden konnten, dass da keine virtuosen Passagen enthalten sind. Und sicherlich würden Chorsänger und Hörer diese Musik ob ihrer Vielfältigkeit und ihrer umwerfenden harmonischen Sprache sehr genießen: Das ist einfach hinreißend, wie Ward da den Kadenzen aus dem Weg geht oder sie auch unterbricht, bis man sich endlich nur noch zutiefst nach Auflösung und Tonika sehnt, die dann nach vier weiteren Takten endlich kommt. Und die Textvertonung ist ganz schnörkelos und einfach wunderschön.

Erzählen Sie uns doch eine kleine Anekdote von der Aufnahme!

Oh, eine interessante Anekdote ergab sich daraus, dass wir zwei Tonmeister für diese Aufnahme hatten. Einen für die Gamben-Consort, das war unser gewohnter Producer, Philipp Hobbs, der gleichzeitig ein fantastischer Tonmeister ist, und einen anderen, Adrian Peacock, der sehr erfahren in der Zusammenarbeit mit Chören ist, und vor allem in England auch sehr bekannt dafür. Und wir begannen mit ihm aufzunehme - und waren wirklich so schockiert, wie er die Knaben behandelte, dass wir dauern dachten, wir müssten das Jugendamt verständigen: Keine Pausen, er arbeitete unglaublich intensiv und hart, und jedes Mal, wenn der kleinste Fehler passierte, gab es sofort ein fürchterliches Donnerwetter. Wir saßen da und waren gänzlich geplättet: Kein professioneller Musiker würde sich diese Art der Behandlung gefallen lassen! Doch als wir dann im Chor fragten, ob die Sänger das denn in Ordnung fänden, bekamen wir nur die erstaunte Antwort: Oh, das ist vollkommen normal, so bringt man dem Chor bei, diszipliniert zu arbeiten...

Und das hat funktioniert, muss ich sagen! Ich meine, die jüngsten Sänger sind sieben oder acht Jahre, die Solisten auch erst elf oder zwölf - und die Disziplin, die Konzentration und überhaupt das Niveau des Musizierens war eine absolute Freude. Da gab es immer wieder diese Kammermusik-Momente, wenn wir eine Phrase colla parte sangen und spielten und diesen perfekten Kontakt mit den Sängern - den Knaben und auch den Männerstimmen - herstellen konnten: Das war eine wirklich sehr erfreuliche Erfahrung.

Gab es auch etwas, was Ihnen als Gambisten besonders schwerfiel, bei dieser Aufnahme?

Nein, eigentlich nicht, das war wirklich reinster Genuss. Die Gamben-Stimmen sind so gut geschrieben! Wir haben natürlich unsere eigene Herangehensweise an Klang und Intonation, sind vielleicht ein bisschen fanatisch, was Intonation betrifft, so dass es eigentlich ganz normal ist, dass wir beim Stimmen in so eine Art meditativen Zustand verfallen. Daniel Hyde und sein Chor kennen das auch schon von uns, und das war nie ein Problem.

Was, würden Sie sagen, macht Ihre Einspielung dieser Anthems für Sie besonders - wenn es da etwas gibt?

Nun, die Akustik in der Kapelle des Magdalen College Oxford, in der wir aufgenommen haben, ist eine ganz besondere: Lebendig, aber klar. Und natürlich war es auch ein Stück weit bewegend, das letzte Stück - This is a joyful, happy, holy day - auf der Aufnahme in diesem Ambiente zu spielen und aufzunehmen: Das ist ein Stück für den Prince of Wales, Henry Frederick Stuart, das erklang, als er als Prince of Wales eingesetzt wurde. Und Henry war zu Zeiten Wards Student am Magdalen College in Oxford, da sein Londoner Tutor in Oxford studiert hatte - das war so eine Kollateral-Entdeckung, die ich machte, als ich für diese Aufnahme recherchierte. Der König hatte Henry als seinen ältesten Sohn damals höchstpersönlich nach Oxford gebracht, zu welcher Gelegenheit das College übrigens extra für teures Geld eine höchst schnökelige Empore in der Halle bauen ließ und deshalb beinahe bankrott ging.

Auf dem Cover der CD haben wir dann auch das Portrait des Prinzen Henry abgebildet, das in der Halle von Magdalen College hängt. Und dieser Prinz war wirklich eine interessante Persönlichkeit in der englischen Geschichte: Er versprach ein in künstlerischen Hinsichten Goldenes Zeitalter, brach mit seinem Vater, wollte auf der Universität studieren - und spielte Gambe! Leider starb er sehr jung, mit nur 18 Jahren, und man kann heute nur darüber spekulieren, dass die englische Geschichte sich ganz anders entwickelt hätte, wenn er auf den Thron gekommen wäre, statt seines jüngeren Bruders Charles I. - der dann geköpft wurde.

Ein anderes ganz besonderes Stück war auch die vierstimmige Fantazia 6 von Ward: Wir hatten schon einmal für unser Label Linn die fünf- und sechsstimmigen Consorts von Ward aufgenommen, und so ist diese Fantazia nun eine Art Ergänzung. Aber vor allem handelt es sich dabei um das tatsächlich einzige Stück Gambenmusik, das im Detail in einer Quelle aus dem 17. Jahrhundert erwähnt und beschrieben ist. [Es ist nur drei Minuten lang, aber es wird in einem Brief eines Landadeligen namens Darren North ganz wunderbar beschrieben, als „brisk, lusty, yet ... that sturred the blood and raises the spirits, and satisfies the quickness of heart and hand".] Und außerdem ist diese Fantazia vielleicht das experimentellste, modernste vierstimmige Stück dieser Zeit überhaupt, und es hat uns sehr viel Spaß gemacht, das nun endlich auch aufzunehmen.

Developing an already enviable discography with a similar predeliction for English Consort Music, Laurence Dreyfus and his internationally acclaimed ensemble Phantasm advance their exposure of music by John Ward in a second album. This time, joined by the Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford, the microscope is aimed at small-scale instrumental pieces and more substantial sacred works in John Ward: Fantasies and verse anthems (Linn CDK247). Throughout six four-part viol fantasies, and seven accompanied anthems in an hour-long recital, this well-structured selection displays Ward’s energy and ambition, as well as his skill in refined, yet unrestrained music for the chapel of the court. The instrumental ensemble is at once charming and elegant, then fiery and direct with an impressive focus that relishes each individual viol’s rich tone in a rewarding body of sound that unfolds a flowing, seamless musical discourse. Daniel Hyde’s Magdalen choir responds admirably to Ward’s extraordinary word-setting, and confident, well-trained soloists lead naturally into full choir with impressive clarity of text. Including inventive music that is perhaps pointing the way towards Purcell, Dreyfus’s informed liner note unravels the history of Ward’s life and music through the story of his times, and makes an excellent case for further investigation. It does not seem unreasonable to assume that we may, happily, anticipate additional volumes.

Andrew H. King, Feb 2016 - published in Early Music